Providing patients with a big stage: Using theatre to engage a healthcare audience

A look back into the Bridgeable archives at the challenges and rewards of using a theatrical play to communicate research findings: the risks to be managed, the logistics to be coordinated, and the impact that can be made on stakeholders

Author

- Chris Ferguson

- Founder

The medium is the message

Theatre is a powerful medium. When an audience watches a play, they are transported to another world. The world portrayed on stage becomes the viewer’s lived experience. Since a play is enacted by real people on stage, the experience creates a heightened level of intimacy, far beyond watching slides or even a video on a screen.

In 2007, Cooler Solutions was hired to design services for the launch of a new drug for Roche Pharmaceutical’s U.S. affiliate. The mission involved helping the organization to understand patients’ and physicians’ unmet needs, in order to find areas of differentiation within a highly competitive $40 billion diabetes market. The team supporting the launch comprised several hundred people with functions ranging from brand sales and marketing professionals to legal consultants and medical affairs and regulatory personnel. Enrolling this large, cross-organizational team would prove a challenge.

The pharmaceutical industry is extremely conservative and, as a result, their commercialization process has remained largely unchanged since the 1800s. Large teams of sales professionals are sent to “detail” physicians about their product. This approach relies on an informal gift economy, where sales professionals buy lunch for the office staff, give out small gifts, and provide free samples as a means to gain access to physicians. In 2008, the regulatory environment changed, eliminating many of these gifts as a means of gaining access and promoting products. Within a one-year period, this legal change, along with increasing pressures on doctors to see more patients, caused a 20% reduction in physicians who would see sales representatives. Even with this major regulatory change on the horizon, pharmaceutical companies were struggling to develop new approaches to servicing the market. This is due, in large part, to the reliance on accumulated data on salesforce size and structure as a predictive tool for estimating market impact.

When a pharmaceutical company is launching a new product, the most predictable thing to do is look at what worked in the past to estimate future growth. Because of this overreliance on historic data, introducing new services required communicating the unmet needs of physicians and patients in an extremely compelling manner, so that the project stakeholders had the impetus to take action and look for new opportunities. The communication needed to be clear and specific, detailing clear opportunities for innovative new services. Considering the size and magnitude of the change, the medium of communication also needed to be differentiated, so that the internal stakeholders were sent a signal that we were going to be doing things differently with this project.

De-risking for clients and organizations

In order to engage the large and diverse team of stakeholders, Cooler put on a live-action play. In the case of Roche, risk management for this play was twofold: managing their organizational culture’s adversity to risk, as well as the individuals on the client team’s personal risk. Companies can have long memories. With an audience consisting of leaders from across the organization’s functional areas, the members of the client team were hyperaware of their personal associations with the play.

To help sell the clients on the idea, the Cooler team developed storyboards in much the same way we prototype a new service concept. Our designers animated the storyboards and we hired professional voice actors to narrate the story in order to bring the idea to life. Our team of researchers and designers worked closely with Roche’s internal production team. This team had a lot of experience developing videos for internal events and training, so they had invaluable expertise. We developed a plan that detailed how we would leverage the organization’s experience in constructing sets, lighting, and sound and in sourcing actors from the New York area to play roles we needed filled such as sales professionals and doctors. Using the video storyboard, we convinced the team that a play would be a valuable and differentiated way to communicate and engage with the broader organization. The combination of including internal experts and developing high-fidelity examples of how the play would work helped reduce the risk the play for our clients.

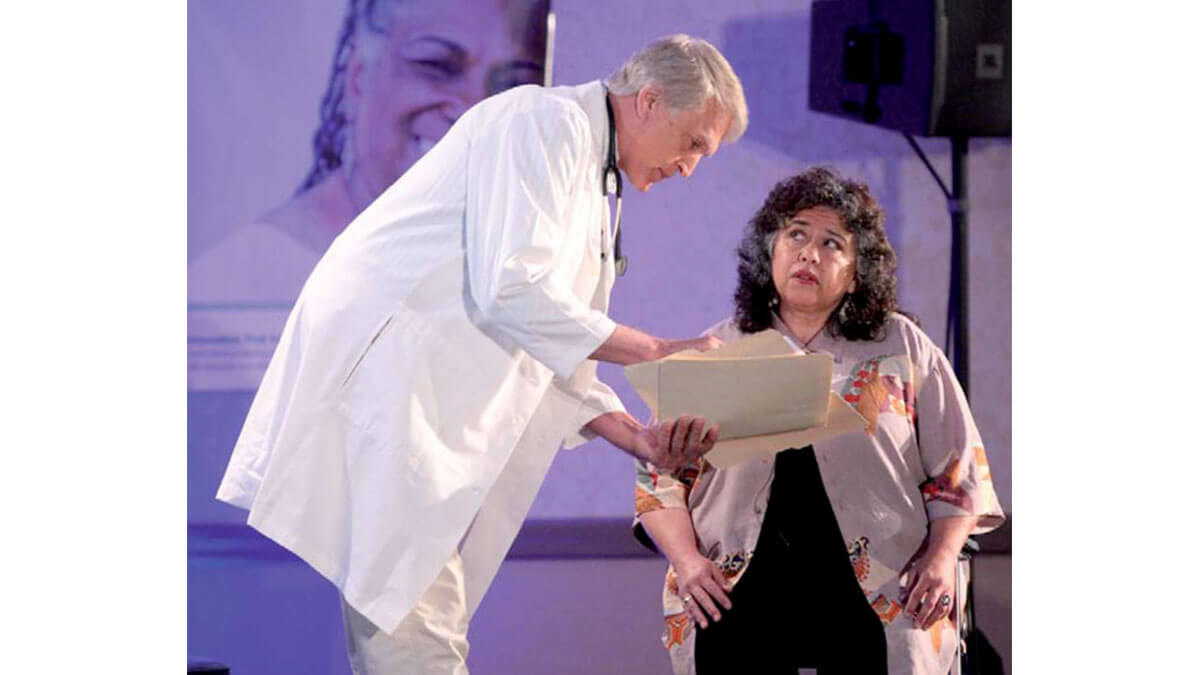

To address the risk-averse organizational culture, execution needed to be flawless. Roles were cast with professional actors and the script was based on verbatim transcripts from the ethnographic study we had completed for the project. Sets were constructed to resemble the actual environments encountered in the field. As a result, the team was able to tell a multilayered story that represented a variety of stakeholders’ viewpoints. The play also needed to deliver our understanding of the diabetes market in a compelling and relevant manner.

Social dynamics, stigma, and stereotypes

There were many benefits to using a play, as compared to traditional means of delivering spoken content. The first benefit was the ability to tell the story of diabetes from the perspective of the patients themselves. Type2 diabetics often face stigma because of a commonly-held assumption that they ‘did this to themselves’. We were able to unpack the social dynamics: issues like external prejudice, along with internal dynamics like avoidance and guilt, were more easily communicated and understood within the context of social relationships between diabetic patients, their friends and family, and their physicians. Within the U.S., diabetes disproportionately affects Latin Americans and African Americans. As a result, many of our research participants came from within these ethnicities. The play allowed us to portray these people as the complex and dynamic human beings we had experienced and not some exaggerated or stereotyped caricature.

Producing a presentation as a play also enabled us to communicate the pain points and preferences of physicians and¬patients in a chronological and contextual frame that much more effectively represented reality than does reducing the multifaceted complexity of diabetes to a slide full of bullet points. The ‘customer journey’ was understood in a more nuanced and, therefore, more valuable way, allowing the audience to see clear opportunities for innovation. We were also able to share complex information with a large number of stakeholders in a relatively raw and ‘real life’ context and with minimal reductionism. Wherever possible, Cooler had included client teams into our fieldwork, as this provides invaluable understanding and commitment to the people we are designing for. With such a large team, this was simply impossible, so the play acted as a comparatively immersive and enveloping experience.

The play followed the main character before, during, and after an appointment with her physician. The storyline was paralleled by a sales professional who is calling on the same physician whom the patient was seeing. The play also involved interactions between patients and other people and between patients and their physicians. The script was based on transcripts from immersions with patients, observations with patient-physician interactions and from ‘ridealongs’ with sales professionals to hospitals and physicians offices. The play was performed in three acts, with a narrator calling out specific insights after each performance. Between acts, the entire group broke out into facilitated workshops where participants identified opportunities to develop services or tactics that would address the pain points and preferences the actors had just presented.

This, in turn, deepened the understanding and increased buy-in by the broader organization. Producing a largescale play within the context of a large pharmaceutical organization was incredibly complex and risky. In the end, five pilots were launched resulting in two new in-market services. The first is a social network where diabetics can talk to one another about how to understand and cope with the disease. The second is a live video detailing service that provides a video link between pharmaceutical representatives and physicians on their computers. Live video detailing gives physicians 24/7 access to disease state information and the ability to order samples and schedule visits from a pharmaceutical sales representative from any location with an Internet connection. Both have been extremely successful and have been scaled up since their launch, proving to be a success in a completely new commercialization model.

If we hadn’t been able to use a live play to convey research insights, it would have been extremely difficult to achieve buy-in to design these two new services. By applying theatrical methods, our research was effectively translated into innovative new services that are bringing tremendous value to both physicians and the diabetic patients whom they treat.