Life and death data

Merging qualitative and quantitative approaches to improve patient engagement

Author

- Chris Ferguson

- Founder

This article will address the challenges and opportunities in transforming quantitative data into qualitative experiences for patients. This approach culminated in the design of a shared decision-making service for cancer patients. The service provides patients and health care practitioners with decision-making materials to improve the treatment experience of people with breast and prostate cancer. While quantitative data about treatment options has existed for decades, research proved that patients and physicians had a very different understanding of the consequences and tradeoffs each treatment offered.

Bridging scientific treatment and human experience

Within healthcare systems, our ability to collect quantitative data has never been better. Technological infrastructure and analytics are increasingly accessible and affordable. Meanwhile, our healthcare systems struggle to address the changing patterns of daily life. Patients are regularly frustrated by their inability to understand and manage their own health. In order to bridge this gap, we must design healthcare delivery that effectively merges quantitative data with experiences that are qualitatively improved from the perspective of patients. Regulatory reforms are driving a change towards the inclusion of qualitative elements of patient experience. These reforms are replacing the traditional medical paradigm where the physician made treatment decisions driven by quantitative data. For example, many clinical trials now require that quantitative scientific results must be supported by qualitative reports from the patients. What this means in practical terms is that even if a new treatment outperforms a placebo by objective measures, the treatment benefits must also be reported by the patient. This has led to certain products that demonstrated scientific efficacy being rejected simply because patients did not experience the results as described in the study.

The other major reform coming into place that is driving change within healthcare is the ability for physicians to bill for the time spent educating patients. In the past, patient education was a “nice-to-have” feature of patient-physician interaction. With the requirement for patients to be more involved in decision-making and with physicians now being compensated to spend time on education, the stage is set for new modes of interaction that bridge between objective quantitative data and subjective qualitative realities.

Cancer treatment decision making

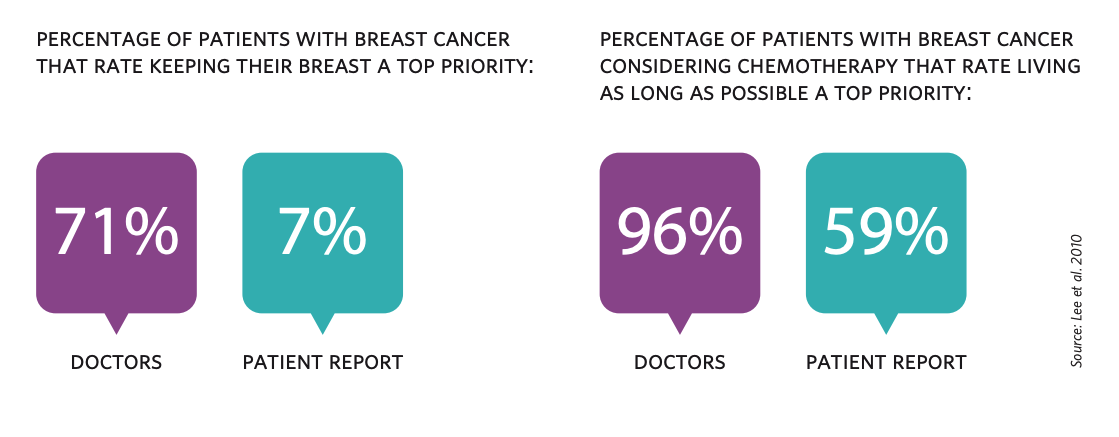

Within cancer treatment, patients have historically had little understanding or input into their own treatment. Physicians have been the principal decision-makers, yet statistics show that physicians do not have an intuitive understanding of their patients’ preferences. For example, doctors believe that 71% of patients with breast cancer rate keeping their breasts as a top priority. The actual figure reported by patients is 7%. Furthermore, doctors believe that 96% of breast cancer patients considering chemotherapy rate living as long as possible a top priority. When you ask patients, only 59% agree that it is a top priority.

Even the experience of receiving a cancer diagnosis can be baffling to some patients: one patient in our study shared their experience of completely misunderstanding the cancer diagnosis that was being communicated to them: “The nurse told me, and she used a big long word I couldn’t even pronounce. She said, ‘you’re taking this really well,’ and I said, ‘that’s because I don’t know what you just said.’” The focus on quantitative survival data alone misses issues of key importance to people about how various treatments would impact their daily life. In cancers where various treatment modalities can be offered, treatment courses tend to be prescribed based on physician specialization preferences. From a purely statistical basis, there was little variation between the survival rates of patients who undergo different treatments. Even if a physician wanted to direct a patient to external resources, no trusted resource exists that is tailored to the communication needs of patients or the treatment impact on their daily life. In fact, one clinician in our study reported: “… the hospital doesn’t have resources to support decisions… 90% of patients are left without treatment support.” Given the historic lack of patient involvement in decision making, we set out to design a shared decision-making service that could effectively educate and empower concordant care.

Identifying knowledge gaps amongst patients

We began by conducting qualitative research with select cancer types that have multiple treatment options and where these options have highly subjective risks and benefits. The cancer types focused on for the study were prostate and breast. Prostate cancer is highly unlikely to be fatal. Treatment options range greatly from observation to surgery and radiation therapy. For most cases, observation is all that is required, although many patients fear the idea of having cancer growing inside them. As one clinician explained: “Patients treat their anxiety with surgery.” A major side effect of prostate surgery is impotence, which can have a significant impact on the quality of life for people who are sexually active. Also, many people confused the term “infertility” with the term “impotence” only to find out the real impact too late. Breast cancer treatments also carry a wide variety of risks and benefits that can have a qualitative impact on people’s lives. More invasive treatments such as surgery can cause limitations in movement, scarring and pain without changing survival rates. Less invasive treatments like chemotherapy can last 2-6 months and affect people’s ability to go back to work or to help out at home.

Designing for engagement

The focus of our project was an online decision support tool that patients, their families and clinicians could use together or independently. The decision support tool is web-based, allowing for access inside clinical settings or into people’s everyday lives. We began our project by partnering with the University of Toronto’s Biomedical Communications Program, one of 4 such programs in the world. Biomedical Communication is an interdisciplinary training that merges visual communication and scientific research to develop images and interactive technology that communicate complex scientific ideas. Together with professors and a graduate from the program, we began a human-centred design approach that included both in situ observation and prototype iteration.

We developed a range of communication styles for communicating key content. For example, we developed definitions of treatment options in a narrative style illustrated with hand sketches and also with a textbook layout. We also designed a wide variety of visual representations of data. We tested survival data using curves, stacked icons, random arrays and various icon types were used to represent the proportion of people who survive every year. The content and overall structure of the decision-making tool was iterated multiple times based on direct feedback from people undergoing cancer treatment. Prototyping helped to determine the rational and emotional impacts on patients and their families. Currently, the decision-making tool is being prepared for the clinical setting with a world-leading cancer treatment centre where it will be incorporated into the cancer services delivered to patients and their families.

The challenges ahead

As we continue to collect and store terabytes of patient data, the real work of designers will be in translating scientific data into the challenges of everyday life. One major challenge ahead is how to help patients set goals and measure preferences when so many important elements of the healthcare experience are fundamentally qualitative. For example, a treatment goal for a person with prostate cancer, such as good sexual function or normal urinary function, is hard for most patients to relate to a numerical value. In order to address this, Bridgeable’s designers have been experimenting with patient cases and personas as a way for people to relate their goals with a patient type who has been through a specific procedure. Another challenge is in how to enroll physicians and the medical community to accept and adopt new forms of decision making.