Ideas by Chantale Bielak

Prototyping policy: Integrating design thinking into policy-making

Author

- Chantale Bielak

- Director, Design Strategy

Why design thinking in government?

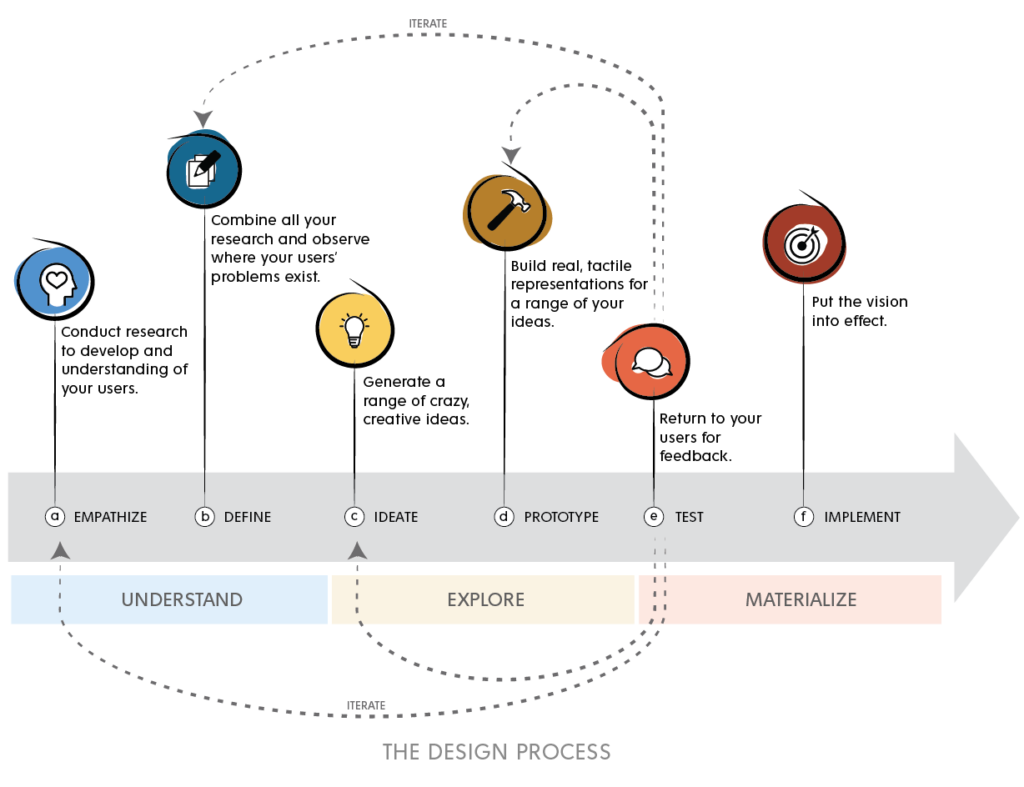

Design thinking is a human-centered approach to problem-solving that starts with people’s needs and advocates for greater empathy. This design process [Figure 1] seeks to understand the people we’re designing for, understand and frame the problem, and co-create innovative solutions that can be prototyped and tested. This approach aims to ensure we are building for the right thing before we start designing a solution.

FIGURE 1 – The design process has 6 main components: a) empathize, b) define, c) ideate, d) prototype, e) test, and f) implement. Adapted from Sarah Gibbons, Design Thinking 101¹

Although this approach has been embraced and used in many private-sector industries for decades, design thinking is increasingly becoming more common in the public sector. Governments are starting to build more in-house teams to help redesign service and program delivery (see one example below), and some are conducting pilots and experiments to ‘prototype’ potential new policies. Even mandate letters are now explicitly acknowledging the need to engage communities and citizens to integrate diverse views into the decision-making process.

Why should design thinking be fully embraced by governments? Because overall, there is still a disconnect between those who make policies and those who deliver government services and programs. This leads to poor service experiences for citizens, fosters a lack of trust among the populace, and signals that following processes and regulations are more important than addressing its citizens’ true needs.

But what would it look like if we redesigned the policy-making process to integrate human-centered design before a policy is made and implemented?

What is a policy, and how is it made?

Governments tend to be risk-averse in how they approach developing and implementing mandates and policies – and for good reason. There are constraints and regulations on governments that simply don’t exist in most other sectors.

To add to the pressure, once the wheels have been set in motion for a plan or policy, it is difficult to pivot, reverse or even stop. Due to this concept of path dependency, things tend to move more cautiously in government (e.g. ‘red tape’?). It’s a constant tug-of-war between knowing that change is needed, actioning it, and avoiding unintended consequences.

“Policy is a more hazy concept, it implies a message or statement of intent which sets a direction of work. Before a policy statement is made, there will be some form of strategic conversation. In governments, this usually takes place at the political level amongst ministers or within political parties and there is little scope for outsiders to enter these spaces.”²

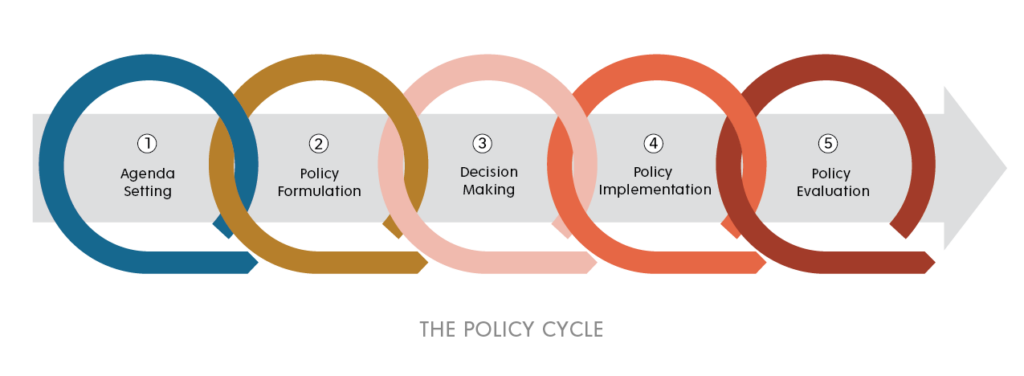

Policies are made by going through a framework called the ‘policy cycle’ [Figure 2], which can be simplified into a sequence of 5 stages: (1) agenda-setting, (2) policy formulation, (3) decision-making, (4) policy implementation, and (5) policy evaluation.

FIGURE 2 – A general framework of the policy process. Adapted from Howlett, M. & Ramesh, M. Studying public policy: Policy cycles and policy subsystems³

In the first stage, before a policy is created, a problem that impacts the public is identified and brought forth as an agenda-setting topic. Then, in the second stage, numerous policy options are developed prior to deciding on the best course of action. Once a decision has been made, governments put the chosen public policy option into effect, then proceed to evaluate and assess whether the policy is achieving its intended goal.

Although the policy-making process is not strictly linear, there is a tendency toward decisions being made in silos with limited horizontal collaboration. This approach inadvertently leads to a disconnect between those who make policies and those who deliver the services and programs, leading to a muddled service experience for citizens.

Another challenge with the policy-making process in its current form is that it remains focused on designing policies from within, and misses the opportunity to meaningfully bring in diverse perspectives from citizens and public servants earlier in the process – well before the policy agenda has been set.

How might we integrate the design process into policy-making?

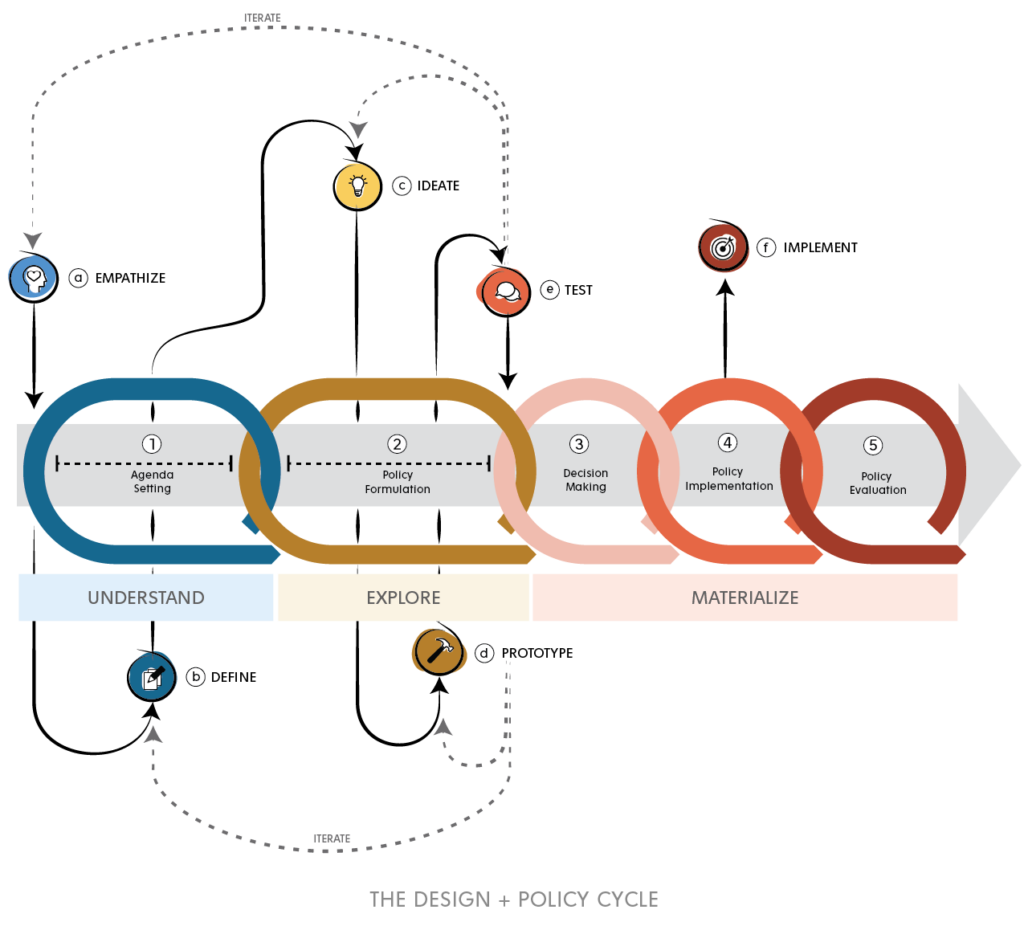

Bringing a human-centered approach to the policy model [Figure 3] involves actively inviting the lived experiences of citizens and public servants to iteratively co-create policies.

FIGURE 3 – A proposed model for integrating human-centered design thinking into the policy-making cycle.

The redesigned model above unifies the policy and design cycles, highlighting two significant shifts:

(1) Empathize and understand users and their problems before the policy agenda has been set, and (2) ideate, prototype, and test policies before an implementation decision has been made.

Each step is outlined below, describing how design thinking impacts each stage of the policy-making cycle.

a – Empathize

Integrating design thinking into the policy-making process means starting with empathy and defining the problem before the agenda setting stage. But how exactly can we do that? There are many different design thinking tools that can be leveraged to meaningfully engage the public. Intensive community consultations, surveys, interviews, and observation sessions, for example, can be conducted to get a clearer picture of who our end-users are and their specific needs and challenges.

b – Define

Based on the insights collected, we can start to frame and define the problem that will be brought forward to the agenda setting stage. A good problem statement is human-centered, and provides a direction for ideation but does not pre-define a solution.

c – Ideate

Once the empathy-driven agenda has been set, we can start to ideate different policy options by inviting a diverse group of stakeholders, ideally including both the public and public servants. Here we can leverage ideation sessions and co-creation workshops, which are fun, creative methods to co-design ideas with users, not for them.

This more inclusive ideate step will serve as an important input into the policy formulation stage, where the development of policy options solely within the government is still common practice.

d – Prototype

The next step is to start prototyping policies, which means testing and experimenting with policy ideas and goals, and exploring potential future outcomes. Prototyping adds a layer of de-risking new policies and ensures that resources are well–considered before implementing policies that don’t work for the people they are meant to serve.

A prototype is a low-resource, quickly designed and tested version of what we are trying to build–in this case, a policy. It’s not uncommon for prototypes to come to life using simple materials like cardboard, post-it notes, digital tools, and interactions like role-playing and simulations. The goal of a prototype is not to arrive at an answer but to go through a process and learn about the strengths and weaknesses of an idea and identify possible new directions.⁴

Read about our work in Prototyping citizen-centric access to electronic health records

e – Test

After developing low-fidelity prototypes, the next step is to test and validate them by running user testing sessions. Another common design thinking methodology used for both prototyping and testing is called a design sprint. Design sprints allow us to focus on solving a clearly defined problem. The process also enables us to quickly build low-fidelity prototypes, and test them with end-users to learn a lot in a short period of time.

Testing low-fidelity prototypes is an important step prior to decision-making and policy implementation as it will allow governments to adjust the policy design or come up with a completely new solution altogether.

Why should we integrate design thinking into policy-making?

“Whether consciously or not, policy programs touch the lives of millions of people, and the unintended consequences or conflicting results from the enactment of poor policies can be extremely harmful. The potential benefits of testing policy goals before they are put in place are therefore huge.”

By approaching policy-making efforts through a design thinking lens rooted in empathy, governments can actively ensure diverse and underrepresented perspectives and voices are brought to the decision-making table. Inviting the citizens and end-users into the early stages of policy-making will enable greater trust, as well as demonstrate a commitment towards the development of policies that are more equitable and inclusive.

Case Study: The role of design in crafting government policy to prevent youth homelessness

To enable this empathy-driven approach, governments will need to expand on their methods and capabilities. By adopting and integrating human-centered design methodologies into the early stages of the policy-making process, governments will be better equipped to create more empathetic policies and programs that truly address their citizens’ needs.

References

1 — Gibbons, S. Design Thinking 101. Nielsen Norman Group. 2016 July 31. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/design-thinking/

2 —Buchanan, C. Prototyping for Policy. Policy Lab, GOV.UK. 2018 November 27. https://openpolicy.blog.gov.uk/2018/11/27/prototyping-for-policy/

3 —Howlett, M. & Ramesh, M. Studying public policy: Policy cycles and policy subsystems. Oxford University Press Canada. 2003.

4 —Kontschieder, V. Prototyping in Policy: What For?!. Stanford Law School. 2018 October 22. https://conferences.law.stanford.edu/prototyping-for-policy/2018/10/22/prototyping-in-policy-what-for/